GRAND RAPIDS HISTORIC DOWNTOWN HOTELS - Written for the Osher Lifelong Learning Class (OLLI) and the Michigan Postcard Club.

Grand Rapids historic hotels include the Amway Grand Plaza Hotel (lobby shown above). The grand opening was New Years Day 1916. The hotel was restored to a new glamour in 1981, jumpstarting Grand Rapids downtown revitalization. Shown above is the lobby, which in 1916 was considered one of the largest in the nation. Photograph by Pam VanderPloeg

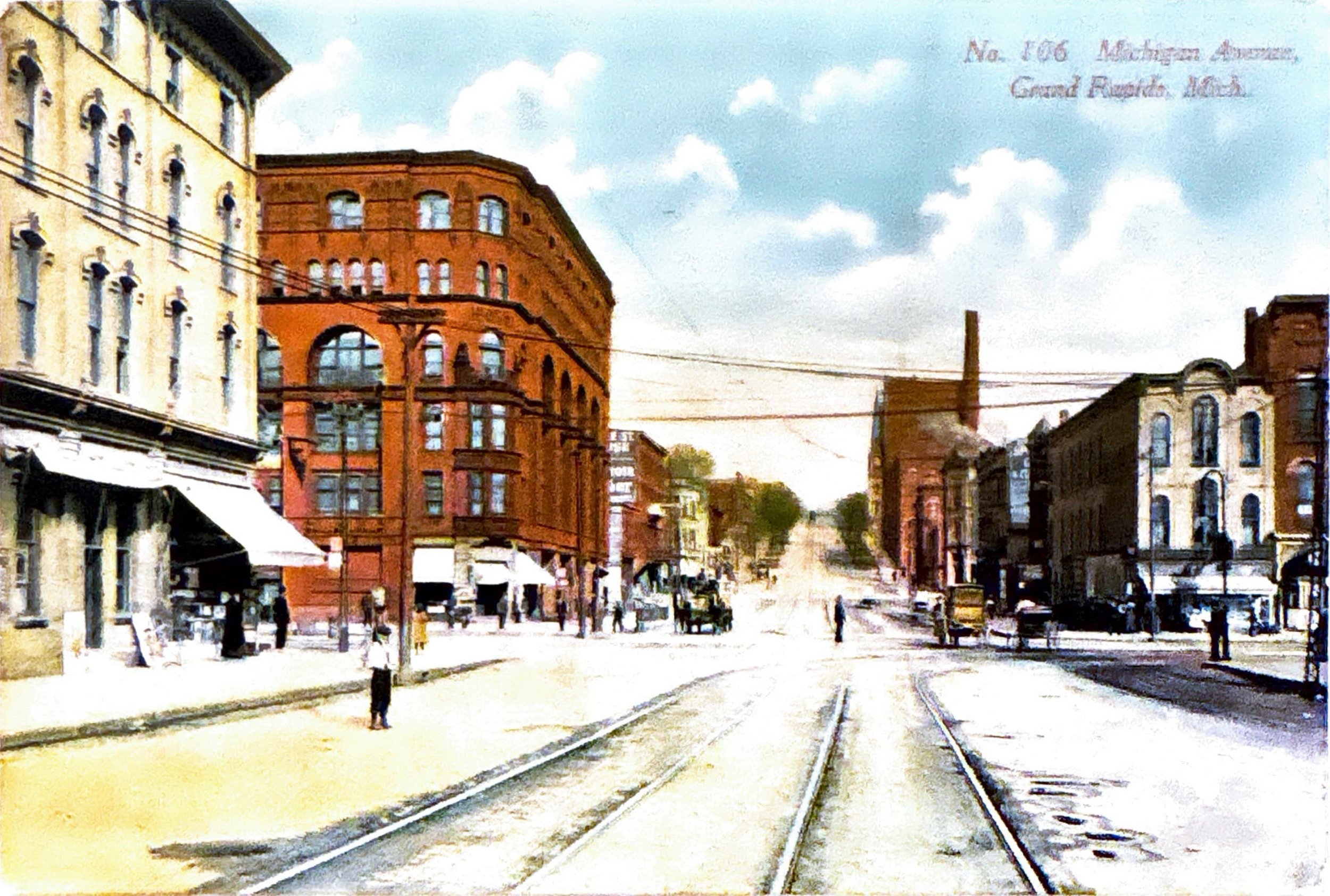

WHAT CAME FIRST: As soon as Grand Rapids was born, wood-frame hotels sprang up on its new streets. However, frequent disastrous fires were common, and by the 1860s, the more fire-resistant brick was replacing wood. Owners soon began to add luxurious interiors. This is a brief story of some of those iconic early hotels. Postcard images are from the collection of M. Christine Byron and used for educational purposes only. Photographs on the second page are by Pam VanderPloeg. Black and white photos of the Cafeteria and Colonial Room are from the digital collection of the Grand Rapids History Center, Grand Rapids Public Library. All images, except for the writers photographs of the Amway Grand Plaza hotel and tower, in this brief history are shared for educational purposes only and are not owned by the writer.

The EAGLE HOTEL, shown above, was completed in 1834 at Louis and Waterloo and operated until 1933. It had countless managers, but only one known for killing a guest (1864). An 1883 fire destroyed the wooden structure, and it was later replaced by the $25,000 red brick building you see in the photo above.

At Division and Fulton, in 1887, cousins of “Buffalo Bill” Cody, opened the CODY HOTEL. Buffalo Bill, a frequent hotel guest, donated the hotel’s unique decor—a bevy of huge buffalo heads for the lobby. Owners claimed the Cody had the world’s most comfortable beds. It’s motto was “The Gateway to Vacationland.”

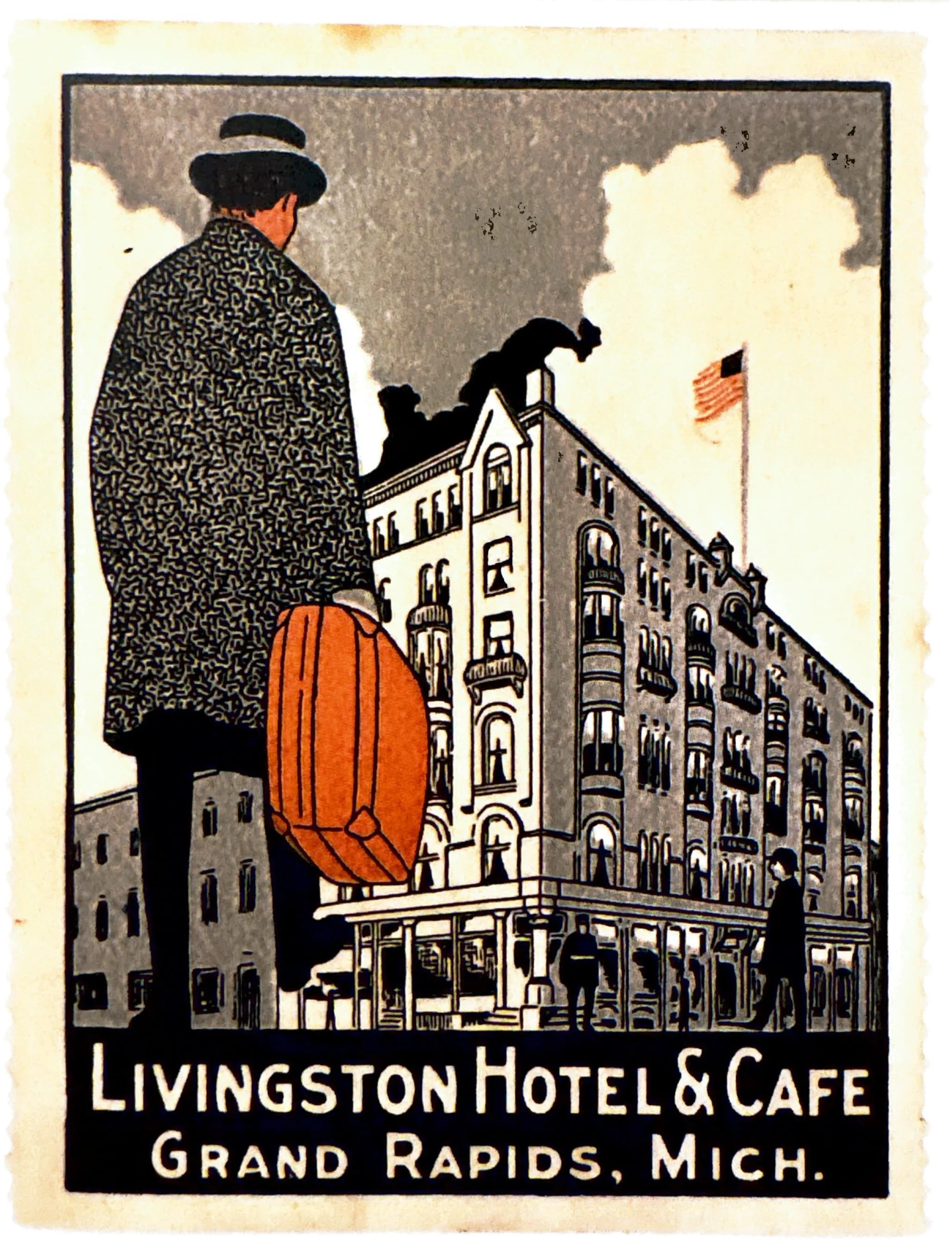

Across Division Street that year, Edward Lowe opened the impressive six-story Livingston Hotel. It had 104 leaded beveled glass windows, but only 9 baths. On April 1, 1925, during a devastating fire centered in the Livingston Hotel’s stairwell, guests tried to escape by jumping to safety from the roof. Seven to nine lives were lost, depending on the account. The burned ruins were a grim reminder to passersby, until the widening of Division in the 1930s finally removed the fire debris.

In 1835, the HINSDALE HOTEL welcomed guests on a site that early settler Louis Campau sold to Hiram and Myron Hinsdale for $200. The Hinsdale’s new owner, Canton Smith renamed it the NATIONAL HOUSE in 1840. Then he promptly left town to prospect for gold in California. The National House burned in 1872 and a Smith descendent, George Morton, built its replacement, the 5-story MORTON HOUSE.

Original Morton House constructed in 1874 and replaced by 1923.

THE PANTLIND HOTEL IS BORN: This is where James Boyd Pantlind enters the picture. JBP was born in Norwalk, Ohio in 1851. He was the son of an innkeeper, and at age 14 was taken under the wing of A. Vorhis Pantlind, his uncle, who according to one report came to Grand Rapids after operating the eating houses of the old Michigan Central Railway in Marshall and other Michigan cities.

Pantlind got his chance to operate his own hotel with Sweet’s Hotel. Back when Louis Campau first arrived in the area, the river was much wider at the spot where Sweet’s Hotel stood. It had four islands. The first stood about where the Amway Grand Plaza Tower was built. The other islands trailed down the river. Martin L. Sweet, a New York native who made a fortune in the grain business and at one time served as Grand Rapids’ mayor, filled in the river between the shoreline and Island number one and on this newly created land, he erected a 4-story hotel around the bank and let rooms for $2 a day. The grand opening of Sweet’s Hotel on September 23, 1969, according to an invitation found in 1980 , featured a grand ball with music by Professor Thomas’ cornet band. Guests to the ball were charged $5 a plate for a “pyramid of roast quail with the wings still on.” Sweet hired two famous chefs away from Newport’s Gilded Age resorts. Wood-burning stoves heated each room and up to 6 men sawed the wood, depending on the guest count.

In 1874, five years later, the entire building was raised four feet when Canal Street was filled in to bring it above flood level. According to one Press report, the hotel operated normally while this was going on and according to a press story, not a dish was broken.

Old Sweet’s Hotel after it was remodeled as the original Pantlind Hotel in 1902.

The year the hotel was raised (not razed), in 1874, was the year J. Boyd Pantlind, at 14, migrated to Michigan to help his uncle, A. Vorhis Pantlind run the Michigan Central Railroad eating houses. Few trains then had dining cars. A.V. and and his partner, Farnham L. Lyon took over the Morton House Hotel and J. Boyd Pantlind served as the bell hop and porter. J.Boyd became the proprietor when he inherited the hotel from his uncle and bought out Lyon. In 1899, President William McKinley stayed at the popular Morton House while on a Republican Party campaign tour. A year earlier, J. Boyd Pantlind turned his attention to another hotel.

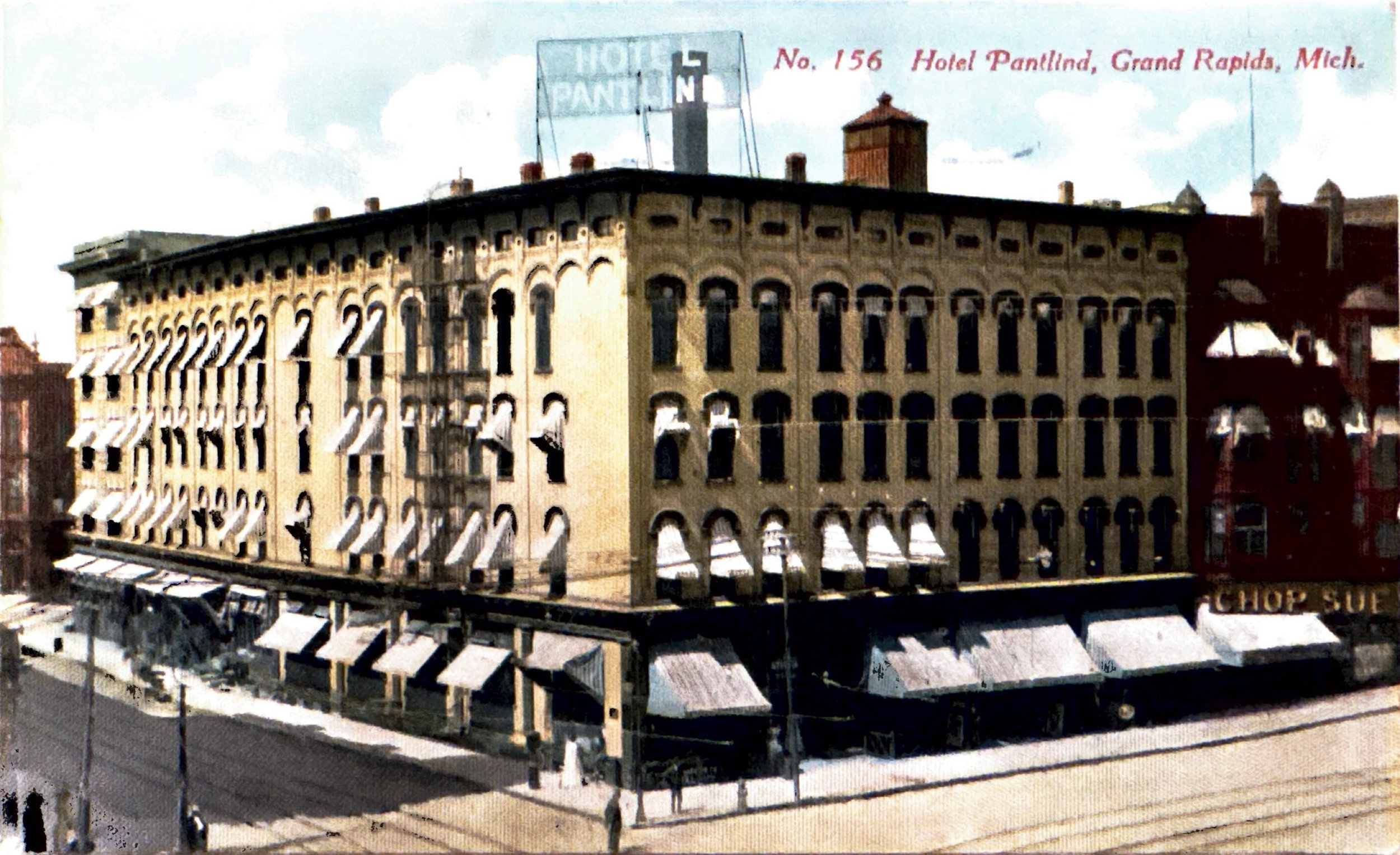

Sometime between 1898 and 1900 (accounts differ), J. Boyd Pantlind bought Sweet’s Hotel. Pantlind renamed it the Pantlind to honor his uncle, A.V. Pantlind. He opened the renovated hotel just in time for the June 1902 Furniture Market. With the remodel, Pantlind had added 97 refurbished guest rooms and a new dining room. Within seven years, 52 additional rooms were added. It was the first hotel in the nation to advertise the European Plan (no breakfast).

AMWAY GRAND PLAZA 2024. Formerly the Pantlind Hotel restored by the Amway Corporation in 1981. The old Sweet Hotel once stood on this site.

Described as the “finest in the city,” the hotel’s popular restaurant generated so much food waste that Pantlind fed the mountains of garbage to the pigs on his 250-acres farm outside the city, where the Woodland Cemetery is off Kalamazoo, today. That saved Pantlind’s pig farm a lot of money, that is, until mayor George Ellis decided it wasn’t a good deal. Ellis won a court case claiming that only city pigs should be allowed to eat city waste (from Lost Restaurants of Grand Rapids by Norma Lewis).

By 1904, the Pantlind Hotel was offering special “Sunday Dinners” to the public thus beginning its history of being the place where families went after church in Grand Rapids.

By 1913, J. Boyd could see that the Pantlind Hotel needed to expand to serve the booming furniture industry and growing convention trade. He formed the Pantlind Hotel Company and the company bought the entire city block, from Pearl to Lyon. They hired Warren & Wetmore, the architects of New York’s Grand Central Station, to design a larger, grander Pantlind Hotel in the Adam-style architecture with Beaux-Arts details.

On September 15, 1913, the GR Press reported that a carload of motors, cement mixers and other things had been shipped by rail from Chicago by the contractor, George A. Fuller to GR for use on the job site. They would try to hire local workers as much as possible but it was likely that most of the structural steel workers would be brought from Chicago (for their expertise, it seems likely). F.A. Mills was the job superintendent and had leased a home for his family at 501 Terrace SE for a period of two years and the duration of the project. Later the derricks and other equipment will be brought in.

The monumental structure was so large that it required engineers to sink caissons and go down to bedrock for the foundation.

“Building the Pantlind Hotel” by Mathias Alten, 1914. Oil on Panel from the Mathias Alten Catalogue Raisonne.

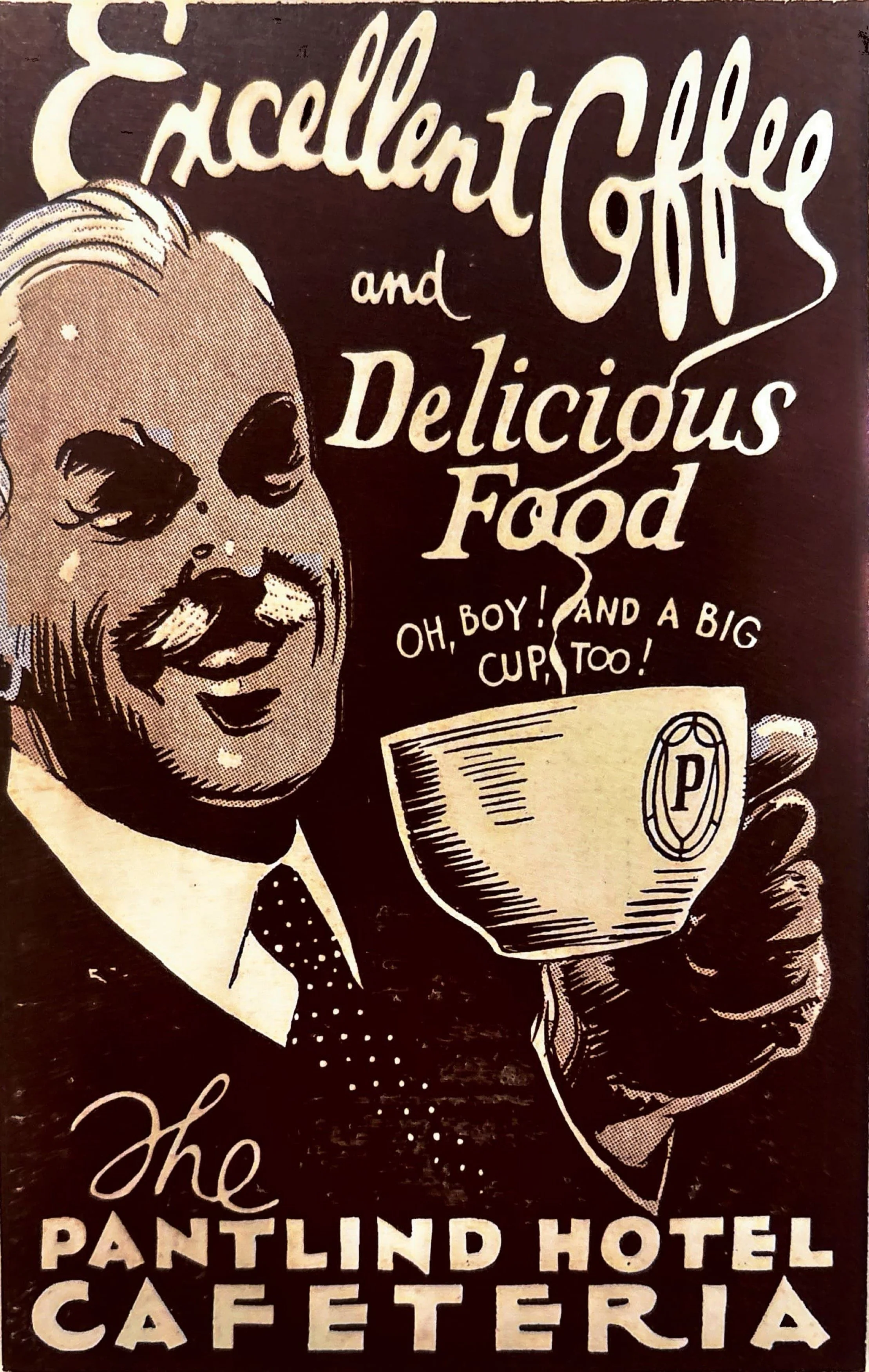

Pantlind Hotel had its own coffee brand.

The Robinson Studio in its description calls out the use of a “platform of two stories upon which the building topped off by a wedding cake swirl of ornament.” historygrandrapids.org Another word used to describe the hotel was “opulent.” The hotel boasted the world’s largest gold-leaf ceiling. The new Pantlind Hotel opened on New Years Day 1916 with 550 rooms and one of the largest lobbies in the nation. The stunning new Pantlind surpassed all other available accommodations.

Again, the hotel’s eateries took center stage. The Cafeteria became a popular destination for local residents as well as travelers. The Colonial Room,was a favorite venue for special occasions. A history of the marketing collateral created for the hotel, reflect the wonderful art of the time.

Pantlind Hotel Colonial Room

By 1922, JBP’s son Fred C. Pantlind took over the management and added 200 more rooms by bringing the north wing up to the 12-story height of the rest of the hotel. The time during which J. Boyd Pantlind and Fred Pantlind ran the establishment was considered the zenith of hotel life in Grand Rapids.

Katherine Pantlind Whinery, Fred Pantlind’s daughter, who was in 1980 considered the oldest living descendent of J. Boyd Pantlind and referred to herself as the matriarch of the Pantlind family, recalled that J. Boyd was short, “rather round,” with “twinkling brown eyes.” Being just one generation away from his family’s Scottish roots, he was considered a competent story teller with a gift for using dialects. “He always had a smile and a marvelous sense of humor,” she said, recalling that he was the most vivid character I ever knew and a “natty dresser, with tailored suits edged by white percale, spats, a bowler hat and glasses attached to a grosgrain ribbon.”

Pantlind Lobby - Possibly 1930s or 1940s.

Pantlind Hotel Cafeteria

Katherine remembered how beautiful the building was when it opened and how the furniture dealers would come twice a year for great dances in the ballroom and famous people would come to stay. She remembered that quite often the family would frequently live in the hotel. Kathleen remembered with great fondness the waitresses, chambermaids, and porters who would often look after and play with the grandchildren. Katherine also remembered it was a difficult time for the hotel during prohibition because the hotel which often lost money on the food would make it up on the liquor. From “Proud Hotel’s History Relived,” Grand Rapids Press, September 11, 1980.

On Christmas Day in 1922, J. Boyd Pantlind died. A small excerpt from his obituary, penned by his powerful business friends, read— “He contributed more to the nation’s happy opinion of Grand Rapids than any other single person who ever gave it the benefits of a long and fruitful career.”

After his death, the hotel passed into other hands. In 1929 the hotel was owned by Joseph Brewer until 1943 when he died. In 1931, the Press reported that the directors of the Furniture Exposition Association met in the Pantlind Hotel’s “Furniture Rooms,” to talk advertising plans. During its storied history, the hotel was a gathering place for visitors attending conventions and the furniture market. It was a place where city clubs and organizations met on a regular basis. Conventions of all manner of groups were frequently held in the hotel in concert with the Civic Auditorium, just across Lyon Street. Families came to the Pantlind to celebrate special occasions. Deals were made and plans were hatched over food and drink that impacted all aspects of city life. The photos of these groups meeting abound in the Robinson photograph collection at the Grand Rapids History Center.

Just before Brewer’s death in 1943, the hotel was taken over by the Army Air Corps which used it and the Civic Auditorium for the Army weather school for the next 9 months. The hotel’s furnishings and equipment were said to have been moved across the street to the Goodspeed Building and it was the first time, the hotel ever closed. After the Army Weather School left, there were worries that the hotel would never open again. The Press reported that the Goodspeeds gave $50,000 to underwrite the opening of the Pantlind. The hotel manager at the time, Tom Walker bought the hotel, remodeled and reopened it to the public again. By 1963, the hotel was purchased by the Roberts brothers, Jack, William, and Charles who may have owned it until 1973, when Amway co-founders Jay Van Andel and Richard DeVos bought it.

It was the 1981 extensive Pantlind hotel restoration by the Amway Corporation which jumpstarted Grand Rapids’ downtown revitalization. Newly renamed the AMWAY GRAND PLAZA, the hotel’s restoration was completed by Marvin DeWinter Associates. The famous Carleton Varney, of the Dorothy Draper firm, gave the hotel’s interior new modern glamor while reviving and respecting its history.

Marvin DeWinter also designed the dramatic glass towering over the new covered motor lobby on Pearl Street, where Campau Street once stood and was then closed at Pearl Street. Two glass-enclosed skywalks connected the hotel to the civic center, and to a 750-car parking ramp south of Pearl Street. The complex also was connected to the Exhibitors Building on Lyon Street at the river. DeWinter planned that the interiors of the Exhibitor Building would be updated so there was a tie in to the hotel and guests could walk all the way through one megastructure. A word about Marvin DeWinter. He was a complete believer in downtown revitalization and its future as a trendy urban destination.

Today the iconic Amway Grand Plaza Hotel has a significant story to tell and is part of Grand Rapids stunning downtown architectural landscape. A $40 million renovation between 2019 and 2021 included replacing the tower glass with a new lighter and more translucent glass, floor to ceiling windows and a reduction of 10% in energy costs. The hotel now has 656 rooms including the tower and historic Pantlind guest rooms. Its bars and food outlets include MDRD, Ruth’s Chris Steak House and The Kitchen by Wolfgang Puck, the Lumber Baron Bar, the Rendezvous, Starbucks, Woodrows Duckpin, as well as four ballrooms, and 42 meeting rooms and conference areas, according to its website.

For more Grand Rapids hotel history, join Pam VanderPloeg at 7pm, Monday, December 1, at the Michigan Postcard Club, which now meets at Trinity United Methodist Church, 1100 Lake Drive. Check out pamvanderploeg.com for Grand Rapids architectural history. Her book Grand Rapids Downtown Buildings can be purchased at the Grand Rapids Public Museum and at Periwinkle Fog, 125 Ottawa NW.